The Youth’s Companion unveils

“The Pledge of

Allegiance”

Bellamy, a former Baptist minister, came up with: “I pledge

allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible,

with liberty and justice for all." It was amended in 1923 to refer to the “flag of

the United States of America” and in 1954 to add “under God.”

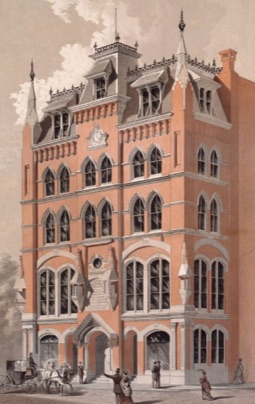

The magazine, first on Washington Street and later on School

Street, Temple Place and finally at 209 Columbus Ave., tirelessly campaigned for the

establishment of a national school day honoring Columbus and on Sept. 8, 1892, it

featured on its pages a model program for a national Columbus Day school celebration. It

was addressed to America’s “Teachers, Superintendents, School Boards and Newspapers.”

“Not one school in America should be left out in this Celebration,” the Companion said.

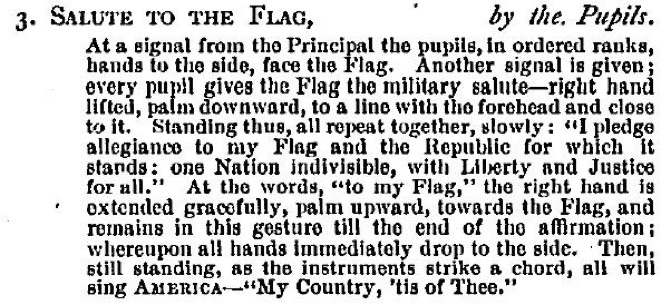

The Companion proposed that on

that Columbus Day, after the reading of the presidential proclamation and the raising of

the flag, students were to participate in the “Salute to the Flag”:

At a signal from the Principal the pupils, in ordered ranks,

hands to the side, face the Flag. Another signal is given; every pupil gives the flag

the military salute — right hand lifted, palm downward, to a line with the forehead and

close to it. Standing thus, all repeat together, slowly, "I pledge allegiance to my

Flag and the Republic for which it stands; one Nation indivisible, with Liberty and

Justice for all." At the words, "to my Flag," the right hand is extended

gracefully, palm upward, toward the Flag, and remains in this gesture till the end of

the affirmation; whereupon all hands immediately drop to the side.

Later the original “Bellamy Salute” was thought to be too

similar to the Nazi salute and was replaced with the hand over the heart gesture. Below,

a copy of the actual description in the Companion.

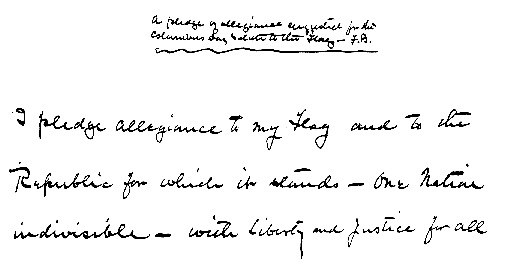

Long after the Companion’s

closing, heirs to Bellamy and his editor, James Upham,

disputed over the authorship of the “Pledge,“ but the U.S. Flag Association in 1939 and

the Library of Congress in 1954 concluded that Bellamy was indeed the author. Below,

Bellamy’s notes, courtesy of the University of Rochester Library.

"The Bellamy salute in 1915." New-York Tribune (via

LOC).

(Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bellamy_salute_1915.jpg#/media/File:Bellamy_salute_1915.jpg

Today, the Companion building at

209 Columbus Ave. is an office/retail building. It is on the National Register of

Historic Places and is often referred to as The Youth’s

Companion building or “The Pledge of Allegiance” building. (Photo by Kathy

Breen.)

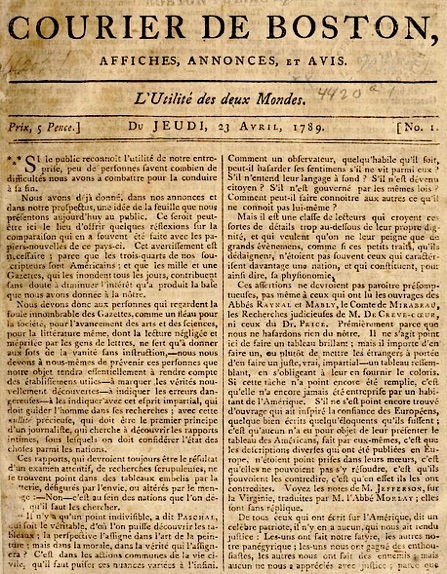

The first

French language newspaper in America--Courier de Boston

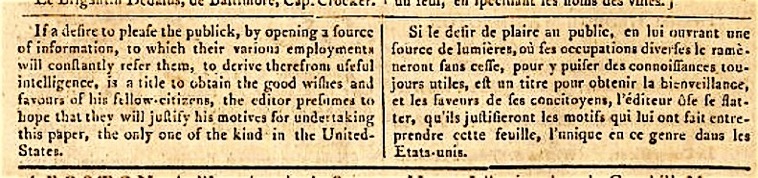

Courier de Boston was the first

French language newspaper in the United States. It first appeared April 23, 1789 and was

edited/published by a Frenchman named Paul Joseph Guérard de Nancrède. It was printed by

Samuel Hall on 53 Cornhill. In his History of Printing in America, Isaiah Thomas

described Hall as “as a correct printer and a judicious editor…industrious, faithful to

his engagements, a respectable citizen and a firm friend to his country” (Thomas 178).

De Nancrède sold books and stationery and taught French at

Harvard University between 1787 and 1800. The newspaper was also sold in Salem, Mass.,

New York, N.Y. and Philadelphia, Pa.

De Nancrède wrote the Courier de

Boston would help local merchants, “that numerous and wealthy part of the

community,” remove obstacles to commerce. He wrote French merchants would be

disadvantaged if they were not “as well informed” and had “unfavourable proofs

respecting the produce, trade and integrity of the United States.”

Finally, he wrote, his newspaper would serve as “the stimulus

to learning French” the “easy and gradual way.” “I’m well aware,” de Nancrède wrote,

“that the undertaking of a paper, in a language, which is not yet prevalent in

America….will be attended with difficulties,” but he said he had “reason to think that

the number of foreign subscribers from Canada, the West-Indies and Europe, will by far

exceed those of America.”

De Nancrède promised to start publishing “as soon as the number

of subscribers will appear sufficient to defray the most necessary expenses.” The paper

was started three months later and lasted six months.

In its first few issues, the paper published exchange rates and

prices of commodities (such as coffee, chocolate, rum wine, butter, syrup and rice) that

could be found in the “principal commercial European centers.” The July 30, 1789 issue

of the paper included a house advertisement, in which the editor asked his readers to

support the paper so it would “become of the utmost utility to the two worlds.” It

suspended publication Oct. 15, 1789.

The first Greek

newspaper in America--

New World

(Νέος Κόσμος)

On March 25,

1892, an MIT student named Constantine Phassoularides from the Aegean island of

Nisyros, published New

World (Νέος Κόσμος). The weekly newspaper lasted a couple

of months (there were about 1800 Greek immigrants living in Massachusetts at the

time) and although historians regularly mention it, no copy of it has ever been

found. There is a record of Phassoularides having attended MIT, but he never

graduated and moved to New York where he worked for several other Greek publications

until his death in 1909.

The Boston

Press Club

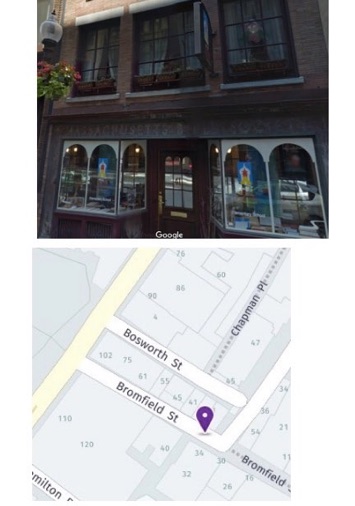

The Boston Press Club was founded in 1886 and was located first

on a loft Court Street and later on the second floor of an apartment at 14 Bosworth St.

overlooking Bromfield Street in downtown Boston. The bookstore of the Massachusetts

Bible Society (“the oldest ecumenical Bible Society in the United States”) occupied the

first floor of the building on the Bromfield side. By 1894 the club had more than 300

members and a restaurant, which provided “wholesome and nutritious” food. Entertainment

speakers included the likes of P.T. Barnum and Mark Twain.

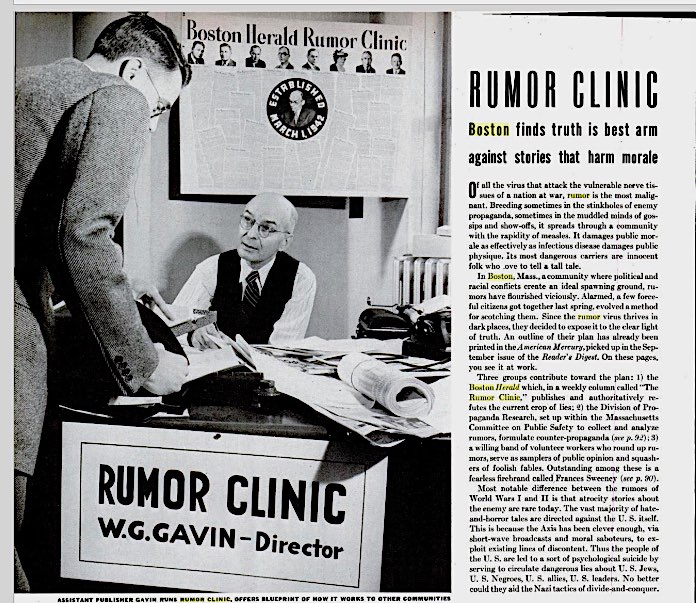

Boston Herald’s publisher Fred E.

Whiting was president in 1894 and oversaw a club that was organized as a “pure

democracy. Neither ‘bigwigs’ nor ‘hightippybobs’” were recognized there. “Within its

doors the man who pays the salary stands upon the same footing as he who receives it,”

wrote club members J.B. Smith and E.C. Howell. In 1895 the club even had its own song,

the “Boston Press Club March.” (William H. Freeman, The Press Club

of Chicago: a History, with Sketches of Other Prominent Press Clubs of the United

States. Chicago: The Press Club of Chicago, 1894, p. 195, accessed Oct. 9,

2017.)